The FBI thought he was dead. Now he's the last living witness to a brutal Louisiana murder

ROCHESTER, N.Y. — Not a day has passed during the past 62 years that Willie Gibson hasn’t thought of Louisiana and the horrific shootings in Monroe that left four of his friends and co-workers dead and a fifth seriously wounded.

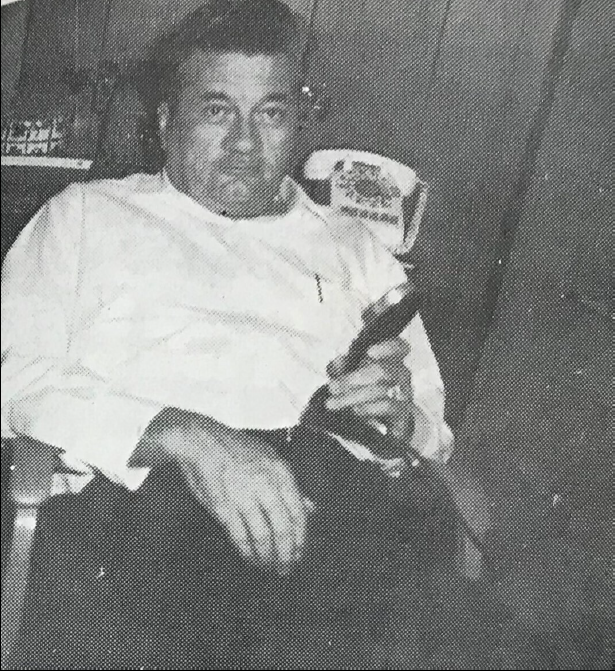

Gibson is the last living witness involved in the events that led to the killings by Robert Fuller, who ran a sanitation business and later became a Ku Klux Klan leader.

And in an interview at his home here, Gibson described publicly for the first time how tensions had boiled over on a job site the day before the shootings in 1960, why he was not there when the shootings occurred and how he fled to New York for his own safety.

Gibson, now 80, provided further support for the idea that Fuller’s eldest son William A. Fuller, who had hit Gibson in the face with a shovel the day before, was involved in the shootings.

His account also shows how shoddy the FBI’s efforts to investigate the case many years later were.

Cold cases: FBI might release thousands of files on Louisiana KKK, civil rights-era murders

During that investigation, which began in 2007, FBI agents mistakenly thought Gibson was the man who had been wounded in the attack. They also did not spend much time looking for him, apparently believing a witness who said Gibson was dead.

Gibson said he believes that Robert Fuller, who claimed he was acting in self-defense, lied about being the lone shooter. Gibson also said that Charles Willis, the man who actually was wounded, told him later that Bill Fuller, then 19, had had a gun and helped shoot the men.

The FBI, which could have learned much from Gibson and other witnesses it failed to find, never investigated Bill Fuller, who was still alive when the bureau closed the case in 2010.

'Mr. Fuller has shot his men': Witnesses haunted by 1960 grisly killings of Black men

The LSU Cold Case Project published a four-part series last fall that outlined multiple inconsistencies in Robert Fuller’s claim that he was fending off an attack by knife-wielding men. The articles also pointed out that Patricia Sherman, the Fullers’ next-door neighbor, had seen Bill Fuller standing next to his father when she ran out into the yard right after the shootings.

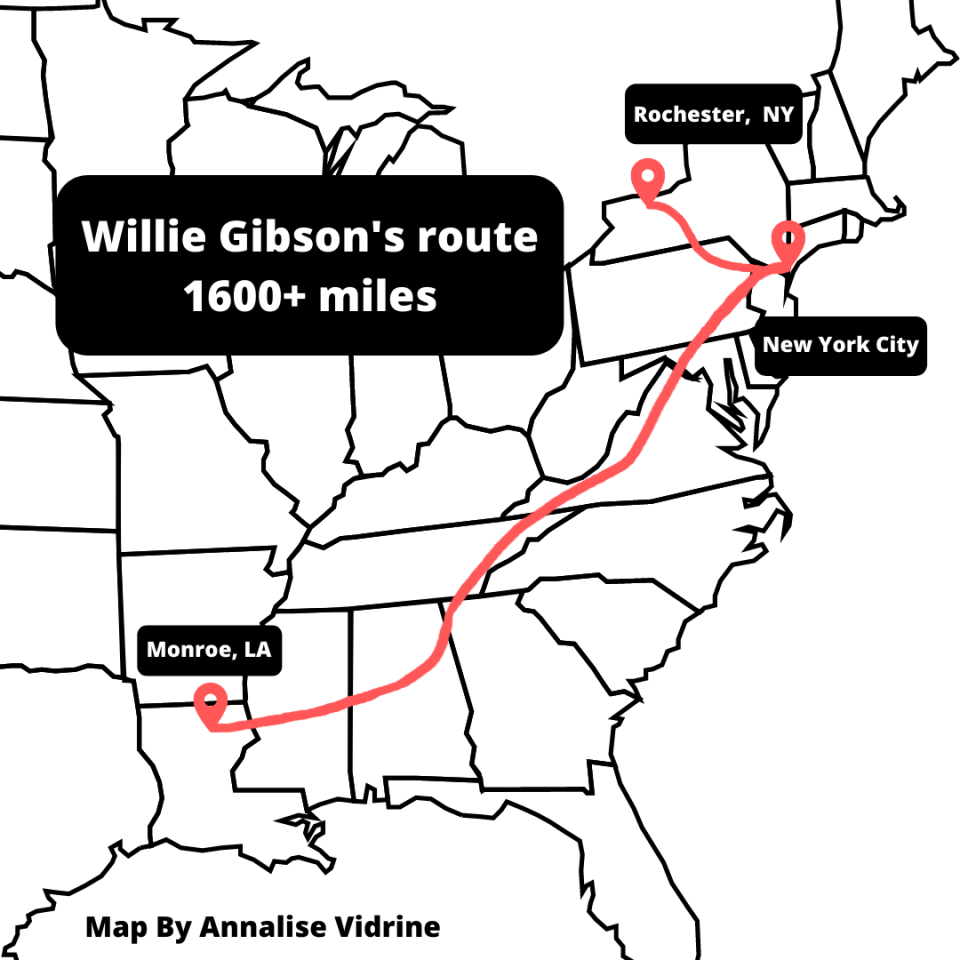

Willie Gibson was located by the journalist Ben Greenberg, working on behalf of PBS Frontline. He put the LSU Cold Case Project in touch with Gibson, who left Monroe the day after the shootings and hitchhiked to New York City to meet his sister, who brought him to Rochester.

As it did last fall, the FBI again refused to comment on its investigation.

'This case flips justice on its head': Victim, not shooter, convicted in 1960 bloodbath

Cynthia Deitle, who headed the FBI’s effort to reexamine the deaths of more than 150 people during the civil rights era, told PBS FRONTLINE that “I feel like I failed the families; I feel like I failed communities.”

Donald W. Washington, a Jones Walker law firm partner in Lafayette, who was U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Louisiana during the FBI's Fuller investigation, said prosecutors from the Department of Justice and FBI agents “worked diligently” on dozens of these cold cases. But, he said, few of the investigations “yielded sufficient evidence or live targets for prosecutions due to the passage of decades of time.”

“The DOJ and civil rights leaders knew that bringing a sense of closure to families and communities by telling them what happened to their relatives and friends was just as important and as impactful to justice as bringing a long overdue, and likely impossible, prosecution,” he added.

'There were higher hopes': Did the FBI fail in trying to resolve civil rights cold cases?

‘We all hung out together’

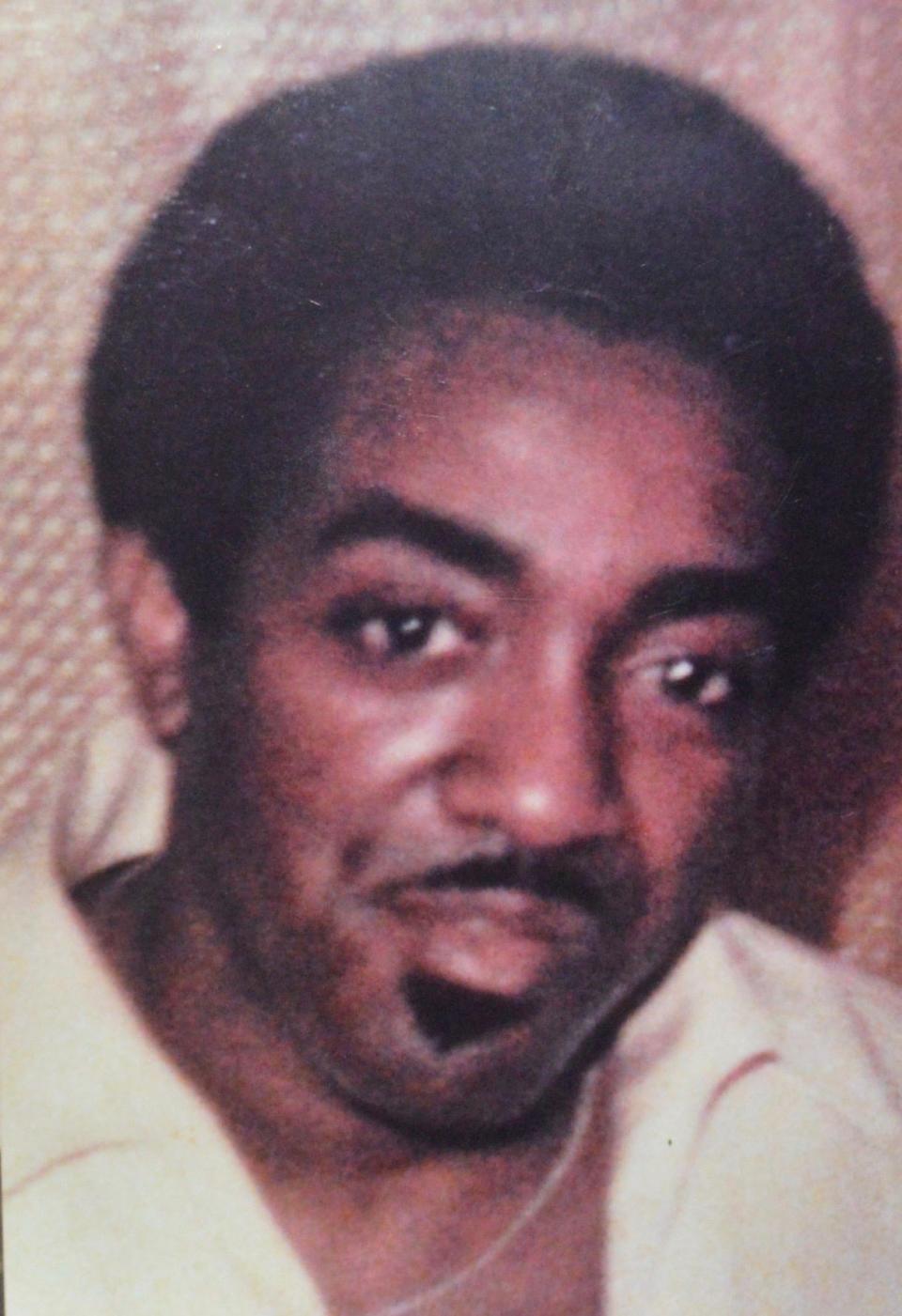

Known as “Gip” by his family and friends, Willie Walters Gibson was born and reared in Monroe, the sixth of eight children.

Gibson went to elementary school with the five men who worked for Fuller on grimy sanitation jobs and were shot that hot July morning in 1960. They included brothers Albert Pitts, Jr. and David Lee Pitts, Earnest McFarland, Alfred “Monk” Marshall and Charlie “Cat” Willis, the lone survivor.

The men lived in the same neighborhood in downtown Monroe and socialized together at the Oak Leaf Bar.

“They were some good boys,” Gibson said in an interview at his home in Rochester. “We all hung out together, went out together on weekends.”

Whacked with a shovel

The day before the shooting, Gibson was at a job site with Robert Fuller, his son Bill Fuller and the five other young Black workers.

Bill Fuller was the only son of Robert Fuller working on the crew, Gibson said, adding that Fuller’s other sons were not old enough to work.

Gibson said Bill Fuller instructed him to go down into an 8-foot-by-8-foot hole for a septic tank and dig out the excess dirt, something neither he nor his father had ever asked Gibson to do before.

Gibson was scared, believing that he could be buried alive.

“I wasn’t going in that hole because I’m claustrophobic,” Gibson recalled.

More cold cases: Almost 60 years later, family still seeks answers in disappearance of La. man

He said he complained to Robert Fuller, who told him to follow Bill’s instructions.

Unhappy with that response, Gibson walked out to the street, where he saw his friends who, minutes earlier, had walked off the job over a separate dispute with the elder Fuller.

Gibson, who could not recall what that dispute was about, asked his friends, “Weren’t you all coming back to work?” They answered no and soon walked away.

Bill Fuller approached Gibson and asked him to come back to work. But Gibson had decided that he was quitting, too.

As he turned to walk away, Gibson said, Bill Fuller suddenly struck him on the left side of his head with a shovel, knocking Gibson to the ground.

Bill Fuller tried to hit Gibson again and missed as Gibson rolled away.

“I guess he was planning on killing me right then and there,” Gibson said.

Gibson said he jumped up and ran only to be chased by Bill Fuller, who insisted that he return to work. Gibson kept running, blood dripping down his face, until he caught up with his friends.

They met up again later that evening at a bar in their neighborhood, where one of the men told Gibson that Robert Fuller had called to invite them to his house the next morning to get their pay.

That raised Gibson’s suspicions. He said he sensed that something was not quite right because the men were usually paid at a bar in their neighborhood, not at Fuller’s house.

“Don’t you all go out there,” Gibson said to the other men, who seemed determined to go to Fuller’s place on the outskirts of town.

“That man is crazy,” he said.

A history of violence: How can a man preach to Black congregations and still be a Klansman?

Fuller’s version of the events

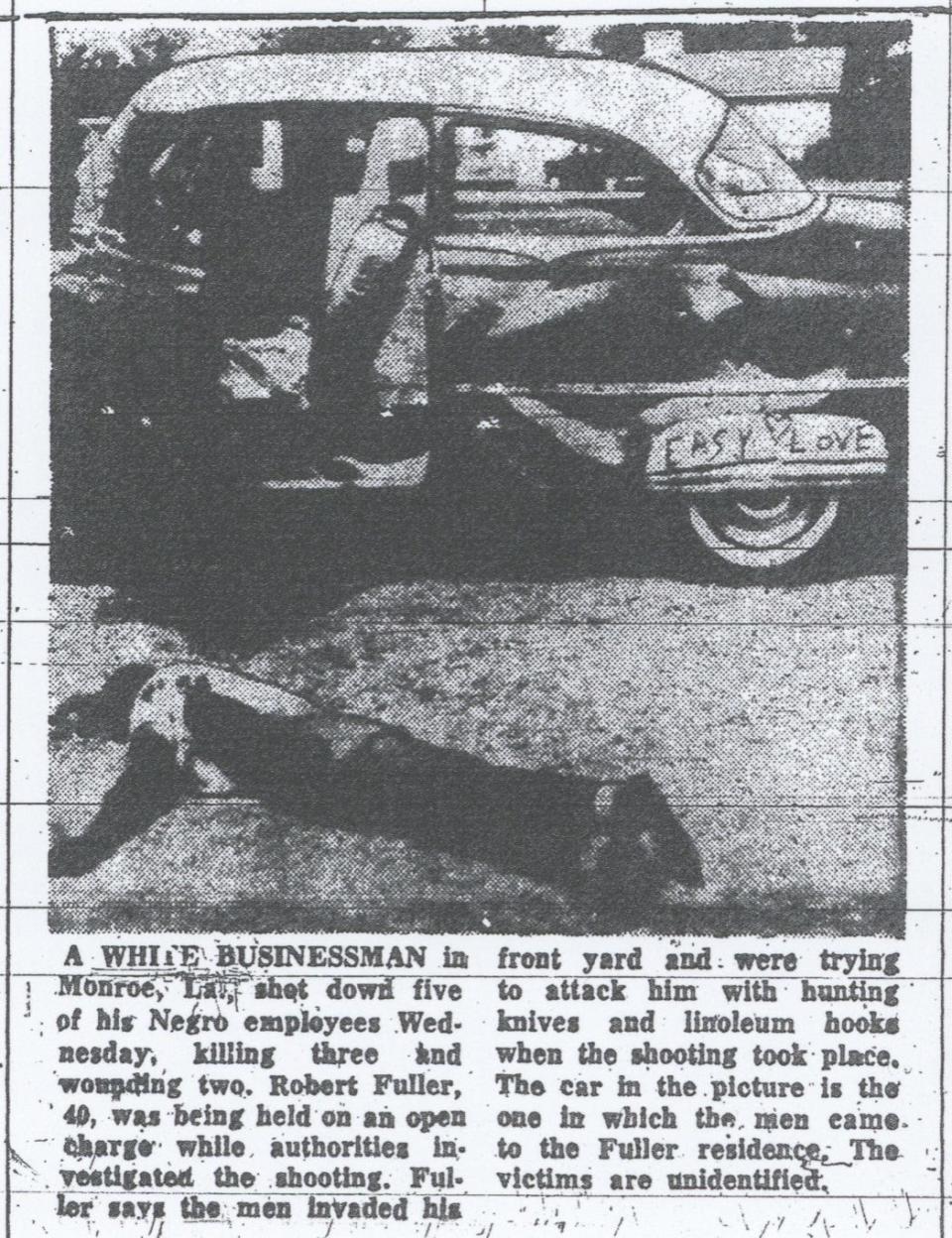

The shootings happened early in the morning on July 13, 1960, and by the end of that day, local newspapers had reported Robert Fuller’s side of the story.

Fuller told the press that Willie Gibson was the cause of all the trouble. Fuller maintained that on the day before the shooting that he had hit Gibson with a shovel because Gibson called him a “white s.o.b.”

Fuller also told reporters that Gibson had been arrested twice in the previous few months for assault and fighting. Gibson said in the interview that he has never been arrested, and neither the Monroe Police Department nor the Ouachita Parish Clerk of Court have any record of any arrests or prosecutions for Willie Gibson in 1960.

Additionally, Fuller claimed that when the young men arrived at his house that morning, they threatened him with knives. In self-defense, he said, he alone shot all five young men with his shotgun, shooting nine shots and reloading four times.

The initial newspaper accounts incorrectly named Gibson as the lone survivor. Within a week, newspapers corrected the error and made it clear that Charlie Willis was the survivor.

Explosive anger: How WWII trauma may have influenced Louisiana Klansman

‘He’s coming to kill you, too’

The day after the shooting, Gibson’s father sat him down on the front porch.

“Fuller killed all the boys. You know he’s coming to kill you, too,” Gibson’s father said.

Gibson said that he did not sense the danger that his father did and said that since he had done nothing, he had nothing to run for. But his father answered, “Well, he’ll kill you anyway because you was working for him.”

Gibson immediately left town on foot with only $12 in his pocket.

“I didn’t have no packing to do,” said Gibson. “I just left.”

“I walked I don’t know how many miles, but I walked a lot of miles on that highway by myself,” he said.

He hitchhiked rides that took him more than 1,300 miles to New York City. A Black truck driver drove him most of the way.

“Come on, get in, you ain’t got to worry about nothing,” Gibson recalls the driver telling him.

As soon as Gibson got in the truck, he fell asleep, and when he awoke, they had arrived in New York City.

Gibson called his brother and sister in Rochester. They drove more than 300 miles to pick him up and took him to their home. He has resided in Rochester ever since, marrying his wife Ora and working various jobs, including in a battery factory.

Family history: How brothers forged new paths away from their father's Klan membership

‘None of those boys carried knives’

Months later, Gibson returned to Monroe, where his old friend Charlie Willis came to visit him at the home of Gibson’s parents.

There, Willis told Gibson that he and their dead friends were ambushed by Fuller and his son Bill.

“Both of them started shooting, and they all were shot right there in Fuller’s yard,” Gibson said Willis told him.

Willis told Gibson that immediately after the shooting, the Fullers placed knives next to each man they had shot to support Fuller’s self-defense claim.

“None of those boys carried knives,” Gibson said.

Authorities in Ouachita Parish called Gibson to testify before the grand jury. Bill Fuller and several Fuller neighbors and sheriff's deputies also were on a list of possible witnesses that still sits in court files.

Gibson recalls going to the courthouse but not what he was asked or what he said.

Willis later pleaded guilty but was only sentenced to five years of probation. He later served some prison time for a probation violation.

The FBI began investigating the shooting in 2007 after a tip from an informant who thought one of Fuller’s younger sons had been involved.

The bureau’s investigative file indicates that an agent looked for Gibson in Monroe but never found where he had lived. The FBI also never located any of his several siblings who still live in Ouachita Parish.

The files indicate that the FBI stopped looking for Gibson when an individual told an agent in 2010 that Gibson was dead, and agents never interviewed Mrs. Sherman, the Fuller’s next-door neighbor.

The FBI closed the case in 2010, noting that both Robert Fuller and the younger son named by the informant were already dead. But Bill Fuller, who was never charged with any crime, was still alive. He died in 2016.

‘Just shot them down for no reason’

Despite all the time that has passed, Gibson said he cannot forget what happened.

“I think about it all the time. It goes through my mind all the time, when they killed all of my boys,” said Gibson with tears in his eyes.

“Just shot them down for no reason. That’s what they did,” he said. “Shot them all down like they were pigeons flying in the air, and they had did nothing.”

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Daily Advertiser: Witness to Louisiana cold case KKK murder tells his story

money

money