Amid COVID surge, these schools have stayed open. Leaders explain how they're doing it.

The omicron COVID-19 variant couldn't have hit at a worse time for U.S. schools. As consensus solidified that schools should strive to stay open, the mutation riddled staff and students with often mild but isolation-inducing illness.

Disruptions hit a new high last week: More than 7,000 campuses closed or went virtual for at least one day, according to the most recent data from school tracker Burbio, up from about 5,500 the week prior.

Many extended the long weekend by an extra day to deal with staff shortages. Others called in parents, police officers and even the National Guard to help.

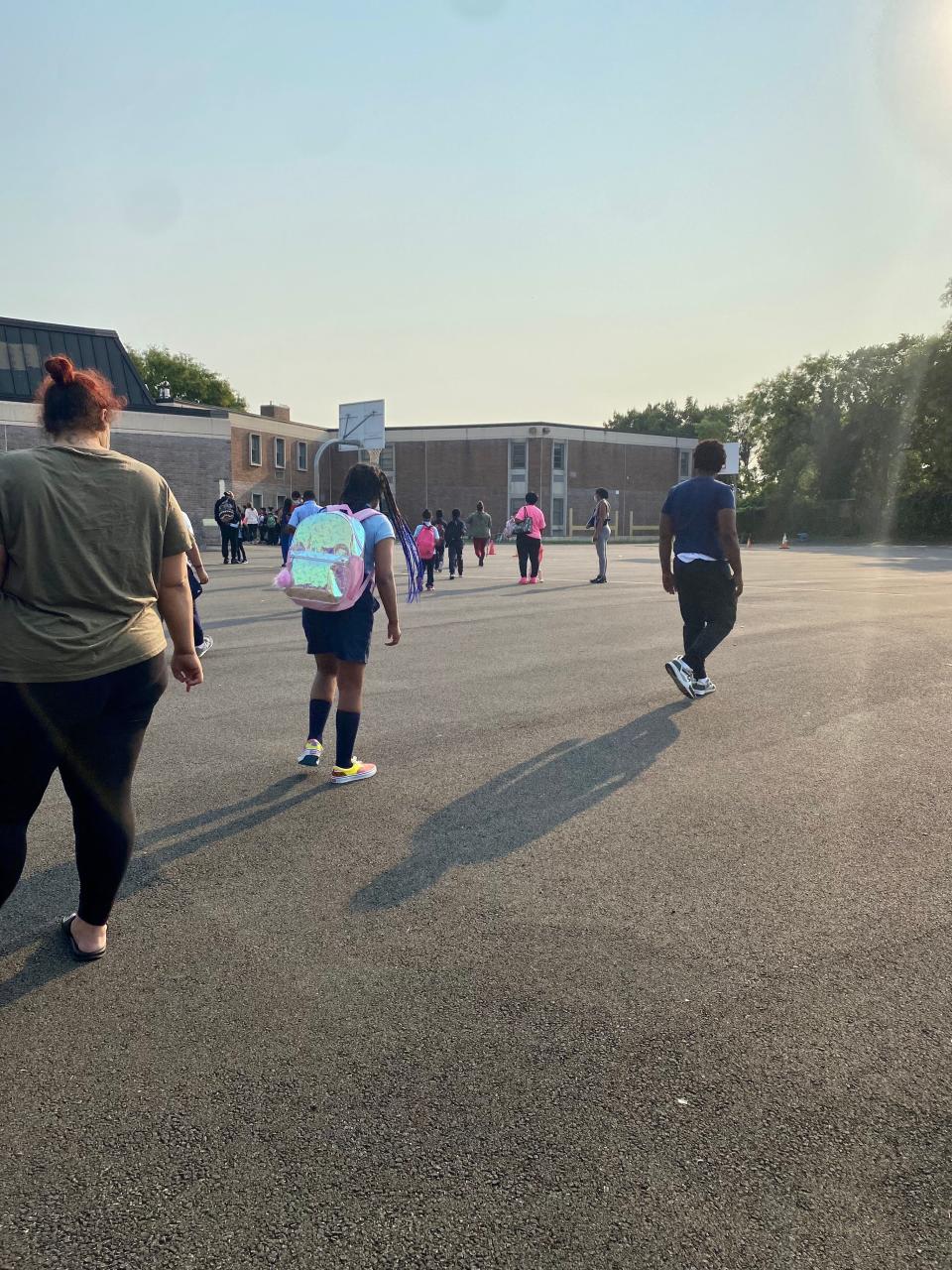

In all, thousands of schools stayed open despite the surge, even in dense cities with significantly high transmission. Here's how some schools went extra lengths to keep disruptions to children to a minimum.

Philadelphia: A 'surgical approach'

Philadelphia faced well-publicized struggles to keep schools open. Positive cases driving staff shortages forced 90 schools into virtual learning at the start of second semester.

But more than 100 district schools in Philadelphia stayed fully open during the omicron surge – at a time when almost 1 in 3 COVID-19 tests in the city were coming back positive. And as of Wednesday, the number of schools operating virtually had dropped to just 14, district data showed.

“We decided to take a more surgical approach,” said Bill Hite, superintendent of Philadelphia Public Schools. “The fact that we would consider closing all schools doesn’t make a lot of sense, nor is it serving children.”

Philadelphia's teachers union pushed back, saying heightened protocols were necessary for safety. The district was still working to secure higher-grade masks for staff in mid-January, for example.

But more than 85% of staff are vaccinated, and even they must take a COVID-19 test weekly. Unvaccinated staff must test twice as often. Philadelphia’s health department has since released more guidance aimed at maximizing in-class time, saying schools should only close because of a staff shortage, not high case counts.

To help support isolated and quarantined students learning virtually, Philadelphia assigns them a quarantine teacher who coordinates with their main educators and specialists.

Chicago: A shortened school day

Chicago Public Schools locked out hundreds of thousands of students for five days in early January while the teachers union and district leaders battled over reopening protocols.

But other public school students in the city spent that time in class.

Noble Schools, a network of public charters serving 12,700 middle and high school students in Chicago kept most campuses open since Jan. 4 – in part by adopting a half-day schedule that sends kids home with lunch after a long morning session.

“The biggest risk of COVID transmission is at lunch, when kids are unmasked and eating,” said David Brown, Noble’s spokesperson.

The part-day schedule will be in effect until at least Jan. 28. In the meantime, students are expected to complete more homework each day.

Noble also installed air purifiers in all classrooms and sent home 6,000 at-home COVID tests over break. Students and staff must wear surgical or N95-grade masks this semester, and the schools secured 125,000 surgical masks. The network in February intends to increase testing by requiring students to opt out of COVID-19 tests, rather than opting in.

The network also doubled the size of its contact tracing team, which works 12 hours a day, seven days of the week to investigate cases, Brown said.

“We didn’t want to put a blanket closure on the network,” he added. “Even if 30% of the (auxiliary) staff is out, but all the teachers are available, you can have a school day.”

Chicago teachers' virtual walkout: Will there be more strikes as omicron surges?

Los Angeles: Aggressive testing

Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest district, has kept most schools open and tamped down infections by moving early on vaccine mandates and aggressive COVID-19 testing.

All staff are now vaccinated or have an approved exemption, according to the district. A student vaccine mandate has been pushed to fall.

The district required staff and students to produce a negative COVID-19 test result before returning after the holiday break, which revealed up to 78,000 infections, according to news reports. But those students and staff then isolated instead of returning immediately and potentially infecting others, even if the trade-off was some days of high absences.

Pandemic absences: The unprecedented quest to find missing students

The district has continued its ambitious testing program, which tests all 500,000 students and staff every week, regardless of vaccination status. And it adopted “test-to-stay” protocols that shorten or eliminate isolation time for students exposed to positive cases, but who don’t show symptoms and who continue to test negative for the virus.

The protocol was recently endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but many local health departments and schools haven't signed on.

As of Jan. 21, all L.A. schools were open, district data showed. That's important for academics as well as students' mental health. The district used federal relief money to hire 331 additional school-based social workers last semester.

A wellness hotline for families and students started earlier in the pandemic continues to be popular, district officials said. Workers there have fielded more than 35,000 calls for assistance on everything from mental health to housing insecurity.

Suburban Atlanta: Reviewing every COVID case

At the start of the school year, Mary Elizabeth Davis, the superintendent of Georgia's Henry County Schools, had been optimistic. Infections were down, vaccinations were up.

Then came delta, and then omicron. “Every single day is a relentless challenge," she said.

A COVID response team of Davis and other district leaders gathers virtually daily to assess each positive case. They make “precise pivots," troubleshooting a staffing gap and contact tracing, all while taking into account factors such as the severity of illness. Sometimes the meeting lasts an hour and a half.

That has helped keep nearly all 51 Henry County schools fully open. Since Nov. 1, just two classrooms and, at one school, a single grade level have shuttered briefly. Student attendance has remained high, at around 93%.

Collaboration with local medical leaders helped Henry County Schools become the first district in Georgia to be approved as a "closed" vaccine distribution site, meaning it could give its own employees the shots. (Day care workers and private-school teachers in the area are also eligible.) Today, 92% of the district’s staff members are vaccinated, far exceeding the state’s and even the county’s vaccination rate. A $1,000 incentive program helped boost numbers.

Another incentive program – pay raises for substitutes – has helped ameliorate staff shortages. Anyone who doesn’t work in a school is part of the district’s substitute bank. Davis herself has taught Advanced Placement courses and served lunch.

And at least once every quarter, both students and staff participate in what are known as Henry Cares Check-Ins. Participants are asked whether they’re okay and need someone to talk to, whether they feel like they belong at school or at work. The data help schools figure out how to better support individuals who are struggling.

Phoenix: ‘The pushback doesn’t matter’

In a community where COVID-19 positivity is pushing past 30%, Arizona’s Phoenix Union High School District is hardly immune to the staff shortages that have pummeled districts nationwide. Classroom teachers have been sick themselves, or have taken sick days to tend to their own children or parents.

Yet the district, which serves roughly 28,000 teens, has managed to keep disruptions at bay. Since the school year kicked off in August, in fact, not a single school or even classroom in the district has closed down.

Part of that’s because the district's substitutes system has held up. “We’re all hands on deck right now,” said Superintendent Chad Gestson. Teachers fill in for each other during their prep periods and get paid for doing so, as do certified specialists, social workers and other staff. Administrators and other employees are also expected to cover classrooms if no one else is available. Gestson himself is on call.

Masks are required – and they were required even when a state law attempted to prohibit such mandates. Despite “all the noise and the drama and politicizing of masks, we from Day 1 said we were going to do it and not waver,” Gestson said. “What happens on social media doesn’t matter, the pushback doesn’t matter, the hate mail doesn’t matter – (we decided) that we will ignore the noise and follow the science.”

The district also hosts community testing and vaccination clinics on its campuses six days a week. (Ninety-two percent of certified staff have gotten their shots, while just 2 in 3 of the county's adults have had at least one.) At times of high spread, like right now, the district doubles down on mitigation – frequently sanitizing all high-touch areas, for example, and reverting to virtual meetings.

That zealous approach to mitigation has had its detractors, but it’s also attracted families to the district. While public-school enrollment nationally has plummeted, in Phoenix Union it’s grown 4% since last school year. “Families are choosing us because they know we're safe,” Gestson said. “They know that we're going to ignore the drama and just focus on our kids and our staff.”

That focus involves ongoing efforts to better serve students’ social and emotional needs.

Back when classes were still remote, the district launched an initiative known as Every Student, Every Day. Staff members were assigned a list of students, each of whom they’d contact at least once daily. “This isn't, ‘Get your homework done,’” Gestson said. “This is: ‘How are you feeling emotionally?’ ‘Is the electricity still on in your house?’ ‘Do you need food?’”

Through wellness checks, district leaders learned more about the community they serve. Along with an increase in campus counselors, each high school now has a student success coordinator, tapped with helping students work through discipline issues by addressing the underlying issues.

"Our community trusts us, and our parents trust us," Gestson said. "Because we've been saying the same thing for two years.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School leaders say these keys have helped them stay open amid omicron

money

money